Your Daily Dose of Climate Hope: Book Review of Becoming Earth by Ferris Jabr

A magnificent one-stop shop for understanding the current state of humanity's fast-evolving scientific understanding of Earth in the Anthropocene

This book review is syndicated by both The Weekly Anthropocene and Your Daily Dose of Climate Hope.

A while back, I posited in a conversation that in the fast-moving Earth of the Anthropocene, global ecosystems were changing so much and so fast that it might now be impossible to write a book on environmental science that was simultaneously a fully comprehensive overview of the field and reasonably up to date. Becoming Earth, by NYT Magazine and Scientific American contributor Ferris Jabr, has proved me wrong.

This book combines cutting-edge science, deep-time Earth history, and accessible and engaging explanations of the wonders of life in poetic prose that never fails to grip the reader’s interest. It’s comprehensive to a truly astonishing degree, achieving nothing less than a concise and eminently readable one-volume summary of life on Earth.

It has a simple yet profound structure: the book is divided into three sections dubbed Rock, Water, and Air, focused on Earth’s land, oceans, and atmosphere respectively. Each of these three sections contains three deep dives (with accompanying travelogues) into topics roughly corresponding to the “past, present, and future” of these systems, making nine chapters in all. Each chapter is entrancingly rich in information, meticulously detailed, poetically recounted and fascinating enough to make a book in its own right.

The Rock section’s first chapter is “Intraterrestrials,” about subsurface life (a much bigger category than once thought) enlivened with a trip by Jabr to an incredible deep cave laboratory).

“The continents themselves may also be partial constructs of microbial terraforming…

In Earth’s earliest eons, microorganisms — and later fungi and plants — continuously dissolved and degraded rock at a rate much greater than geological processes could accomplish on their own.

In doing so, they would have increased the amount of sediment deposited in deep ocean trenches, thereby cloaking subducting plates of ocean crust in thicker protective layers, flushing more water into the mantle, and ultimately contributing to the creation of new land.”

— “Intraterrestrials,” Becoming Earth, Ferris Jabr

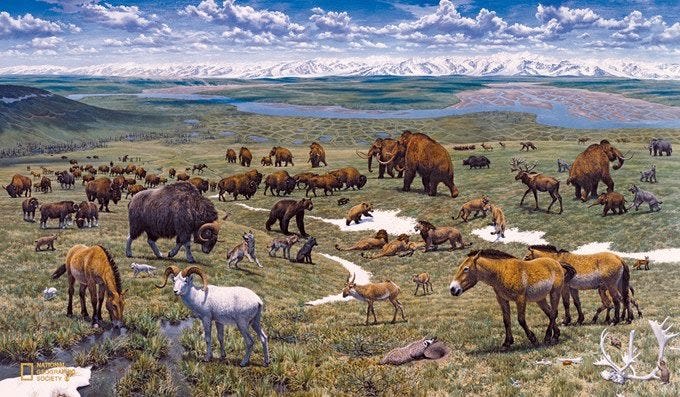

The Rock section’s second chapter is “The Mammoth Steppe and the Elephant’s Footprint” about animal-regulated carbon-sequestering ecosystems, featuring Jabr’s trip to Siberia’s visionary “Pleistocene Park” project.

The Rock section’s third chapter, “A Garden in the Void,” is about soil, ecosystem restoration, and the story of human agriculture, illustrated by Jabr and his husband’s work to restore the soil in their own backyard.

The Water section’s first chapter is “Sea Cells,” about the incredible diversity and importance of plankton from atmosphere-shaping cyanobacteria to chalk-forming coccolithophores and more, with a visit to a research lab studying Narragansett Bay.

The Water section’s second, “These Great Aquatic Forests,” covers seaweed, with trips to Pacific kelp forests and Atlantic kelp farms.

The Water section’s third chapter “Plastic Planet,” is unsurprisingly about plastics, with a trip to a historically plastic-strewn Hawaii beach.

The Air section’s first chapter, “A Bubble of Breath,” is about plants and microbes influencing weather by providing “biological aerosol” nuclei for precipitation droplets to form around, with a trip by Jabr to the vertiginous Amazon Tall Tower Observatory in Brazil.

“Rainforests and other highly vegetated areas emit a melange of large biological aerosols…including virus, microbes, algae, and pollen grains; the spores of fungi, mosses, and ferns; bits of leaves and bark…

This levitating assemblage of life and its vestiges can seed both clouds and ice crystals, sighnificantly increasingly the likelihood of rain and the pace of the water cycle. Above the Amazon rainforest, bioaerosols comprise more than 80 percent of all airborne particles…

Clouds are also biological, sprinkled with microbes and spores, strewn with the remnants of life, forming in the ancient exhalations of living creatures.”

— “A Bubble of Breath,” Becoming Earth, Ferris Jabr

“The Roots of Fire” is on plants’ ancient coevolution with fire, illustrated by a trip to prescribed burns in Northern California. And the third chapter of the Air section, “Winds of Change,” provides an unusually up-to-date summary of the familiar story of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, climate change, and the accelerating renewables revolution.

Throughout all of these chapters, Jabr excels at pulling together existing morsels of information to form a fascinating new whole that subtly transforms the reader’s understanding of the planet they live on. Take this quote from “Plastic Planet” comparing humans’ production of plastic to previous occasions when life-forms made novel substances common on Earth:

“Plastic is yet another way of rearranging existing molecules. One could argue that modern synthetic plastics constitute molecular configurations that evolution would never have discovered on its own. Another way to look at it is that evolution discovered plastic through us. The trouble with plastic is not that it is unnatural, but that it is, like oxygen and lignin before it, entirely unfamiliar to the Earth system and its longstanding rhythms.”

— “Plastic Planet,” Becoming Earth, Ferris Jabr

For context, it’s somewhat common knowledge that Earth’s atmosphere was oxygen-poor until cyanobacteria started photosynthesizing in the Proterozoic around 2.4 billion years ago, kicking off the Great Oxygenation Event and likely causing a mass extinction of most other microbial life at the time.

It’s somewhat less common knowledge that the evolution of woody plants in the Devonian and Carboniferous periods around 300 to 400 million (0.3-0.4 billion) years ago led to a huge buildup of lignin (the class of molecules in plant cells wells that make wood tough), possibly sequestering so much carbon that it plunged Earth into an ice age until bacteria and fungi evolved that were able to digest lignin and put it back in circulation. Jabr pulls together these grand operas of deep-historical geobiochemistry to provide context for the extraordinary moments of the Anthropocene, both underscoring the epoch-defining, planet-shaping scope of what humanity and counterintuitively providing some comfort that now is not the first time that boldly questing Earth-born life-forms have caused massive consequences beyond their control.

There are profound and fascinating stories like this in every chapter of Becoming Earth, and sometimes on every page. It often reads like the sort of book this newsletter would have been proud to write, referencing many of the most paradigm-shifting environmental science discoveries and inspiring real-world ecological actions that have appeared in recent years.

The epic saga of the huge grassroots agroforestry movement in the impoverished Sahelian nation of Niger? That’s in here.

The way that kelp farming helps protect the immediately surrounding water from ocean acidification? That’s in here.

The Ocean Cleanup and others’ efforts to intercept ocean-bound plastic at river mouths? That’s in here.

Kate Raworth’s “doughnut economics” concept? That’s in here.

The insanely great super-rapid price declines of solar and battery technology in the 2010s and 2020s? That’s in here.

The discovery that mineral-rich dust from a specific part of the Sahara is transported across the ocean by consistent winds to help fertilize the Amazon Rainforest? That’s in here, too.

And beyond the eye-catching new discoveries and single case studies, Becoming Earth provides some of the best introductions available for core ecological concepts — and ongoing scientific debates. Lynn Margulis’ discovery of endosymbiosis, the origin of nigh-omnipresent mitochondria and chloroplasts? James Lovelock’s controversial and evolving Gaia hypothesis? The world-changing transformations of agriculture from the plow to the Haber-Bosch process? The centuries-long story of how America rejected, then re-accepted, the ancient Indigenous landscape management practice of prescribed burns? The Cambrian explosion? Mycorrhizal fungi? Pleistocene megafaunal extinctions? Subsurface carbon sequestration? The vital role of whale feces in the global ecology? All in here. You could teach an Environmental Science 101 class based entirely on Becoming Earth, and somebody should — it would be considerably more comprehensive than the classes available when this writer went to university back in the 2010s.

As a reference work, the book does sometimes suffer through no fault of its own from the kaleidoscopically complex and fast-moving nature of its titanic subject matter. For example, Jabr spends several pages profiling an intriguing kelp farming startup named Running Tide. That company went out of business, rather chaotically, literally the same month (June 2024) that Becoming Earth was published. The figure quoted as an estimate for how much money the Inflation Reduction Act allocates to catalyze clean energy is out of date (in a good way), as uptake of clean energy tax credits has been much higher than predicted. In ten years, some new narrative-weaving, science-summarizing book will surely be required to keep abreast of humanity’s ever-shifting our fascinating, fluctuating Earth.

If that hypothetical future volume is anything like as good as Becoming Earth, we’ll be very, very lucky to have it.

“Life was everywhere that winter morning.

Part of the reason the trees and plants were so crystalline was that they harbored ice-making bacteria.

The snow teemed with microscopic creatures that had evolved to survive the journey from ground to cloud and back again — creatures that not only endured the weather but also changed it.

Beneath my feet, networks of root and fungi, and the multitudes of microanimals they attracted, were still respiring and growing.

Some of the bulbs and tubers I had planted were already pulsing with self-generated heat, preparing to melt the snow and spear the soil.

The many coniferous trees in my neighborhood continued to pull liquid water from deep underground, collect sunlight through frost-sheathed needles, and pour oxygen into the atmosphere.

The world was singing, even if I couldn’t hear it.”

— Becoming Earth, Ferris Jabr

I plan to order the book asap. I recently came across Ferris Jabr's article in Hakai Magazine, "The Lunar Sea," and can't wait to read more.

I will definitely order a few copies!! Thank you for letting us know.