Your Daily Dose of Climate Hope: Interview with Kim Stanley Robinson, Science Fiction Maestro and Utopian

Kim Stanley Robinson is one of human civilization’s greatest living science fiction writers. Author of genre-defining works such as the Hugo Award-winning Mars trilogy, Locus Award-winning The Years of Rice and Salt, Nebula Award-winning 2312, Aurora, and the highly influential cli-fi novel The Ministry for the Future, he was invited to speak at the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference (COP26). This interview is a 2025 follow-up to a previous conversation with Kim Stanley Robinson in 2024.

In the interview below, this writer’s questions and comments are in bold, Mr. Robinson’s words are in regular text, and extra clarification (links, etc) added after the interview are in bold italics or footnotes.

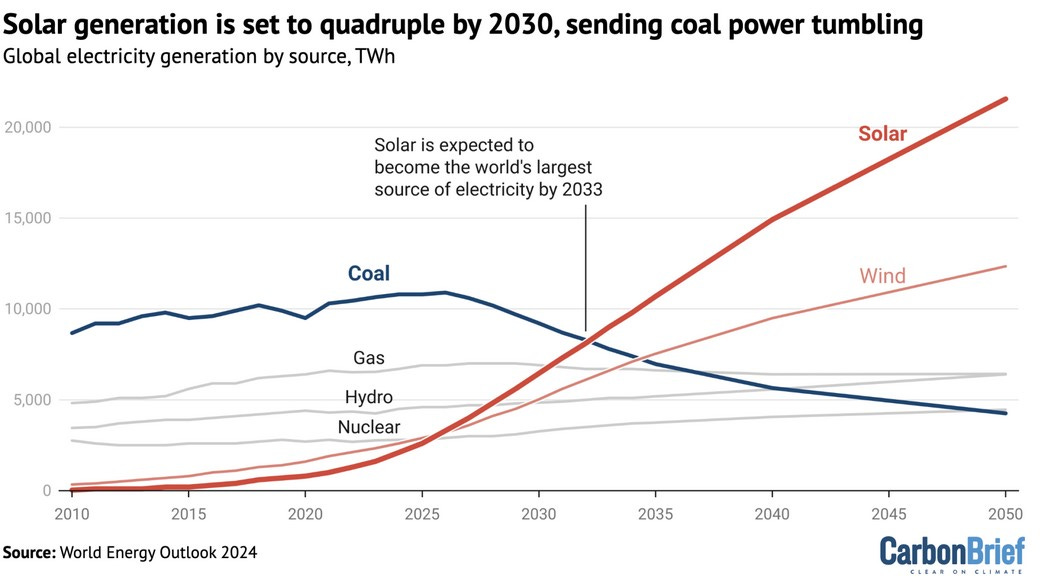

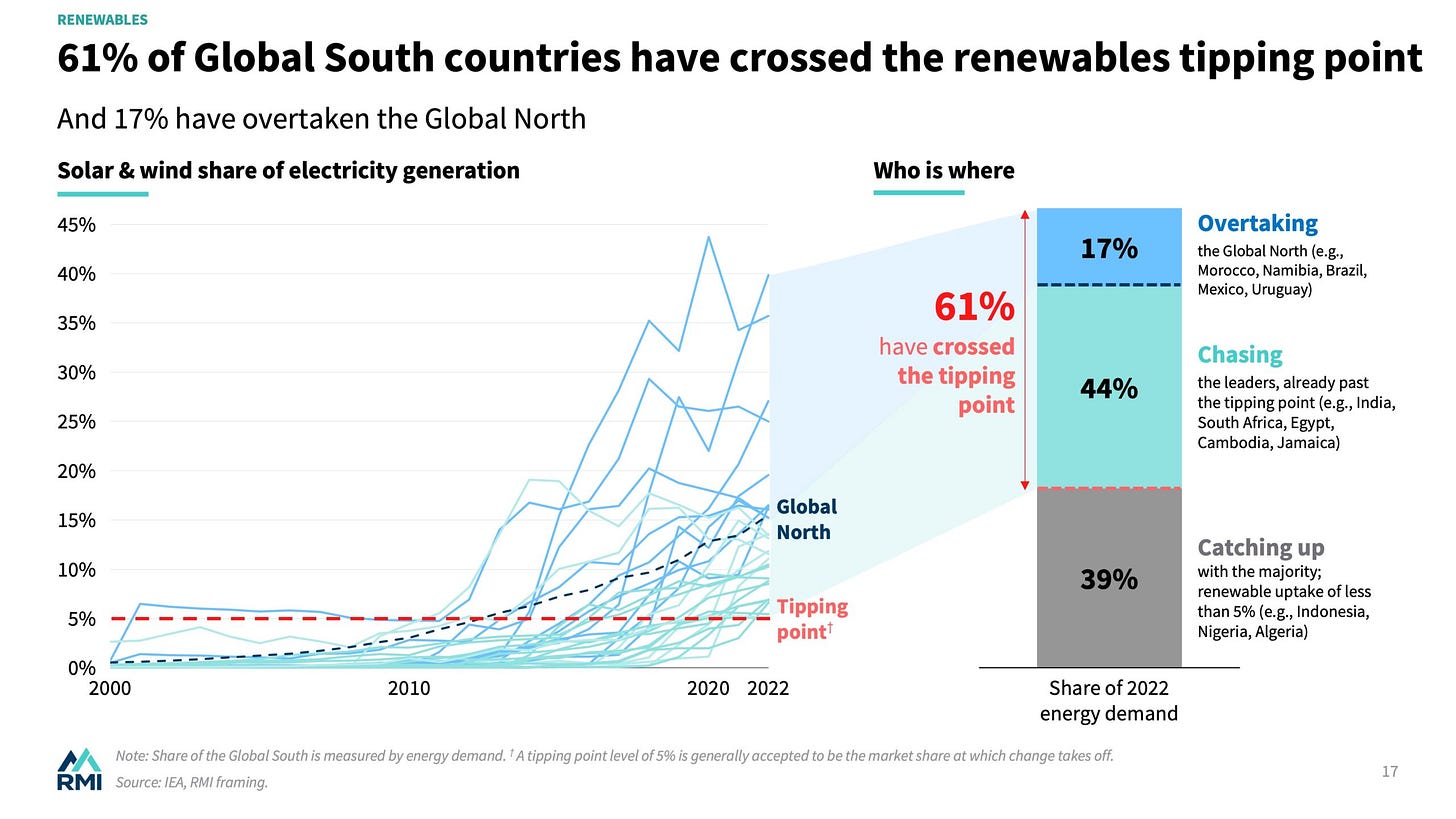

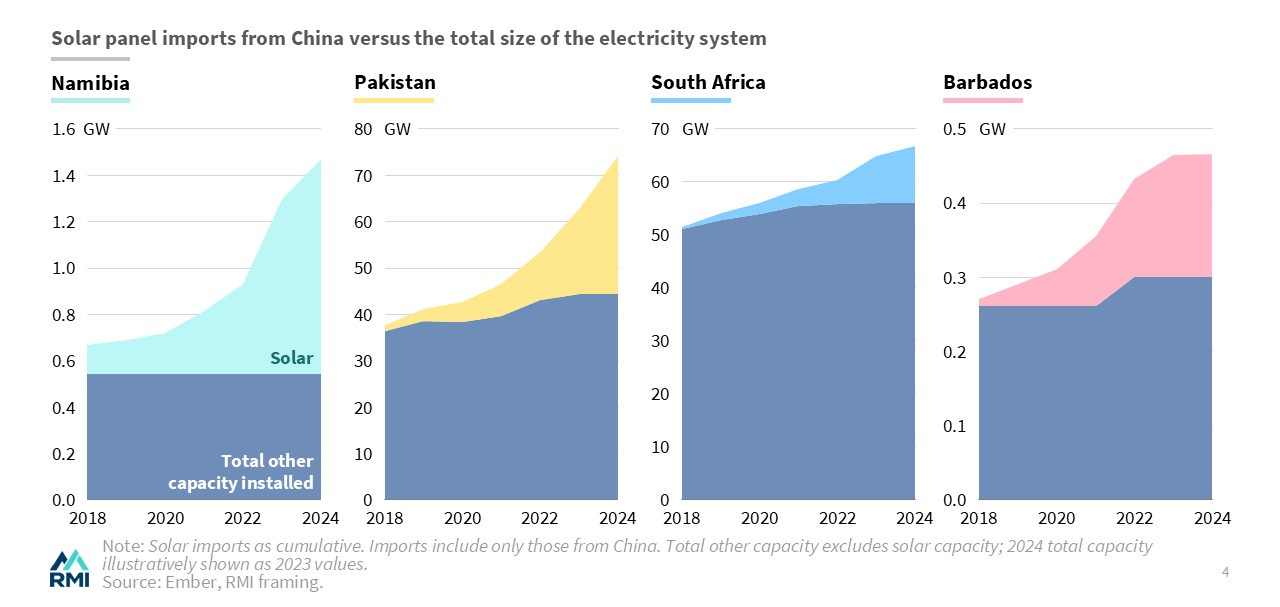

Since our interview last year, the global renewables revolution has accelerated, but America has, after much deliberation, decided to shoot its own foot off. I personally am really encouraged by the renewables news coming out of China, India, other countries in the world. [Here’s a great recent RMI report on rapid renewables growth in the Global South]. But with Trump freezing already-disbursed clean tech loans and stopping wind permits and all this stuff, I'm getting the sense that the world is advancing on renewable energy, but America is relatively falling behind due to our incoming president. What's your take on that?

Well, I'm confused like everybody else, I think, who believes in climate change and believes that people are rational creatures that want a better life for their children. It's mysterious.

It's important to remember that we're talking about a working political majority that is very thin. And that the people who voted for Trump represent about 40% of the U.S. GDP and the people who voted against him represent about 60%. It is important to remember that 51% of the voting public is unimpressed by the Democratic Party's representation of them, or even insulted, and uneducated on larger geopolitics and energy systems.

There's a certain amount of residual sexism: Trump won twice when he ran against a woman and lost when he ran against a man. And there's all these other factors that we all know already.

When it comes to your question about energy, the interesting thing will be in the United States, is there enough momentum towards clean energy just because it's cheaper and easier to install? Will it continue to succeed despite the opposition that we'll see out of the Trump administration? That's an open question. That's a fight to be fought. We'll see what happens.

And you're right to point out in that the rest of the world the clean energy transition is proceeding apace, because it makes sense in multiple ways. It's a jobs program. It's a clean air program. It's a coping with climate change program and a reduction of catastrophes.

One thing I want to end with in terms of this particular question is, especially with the people who know very well that they are contributing to the destruction of the Earth, there's a little bit of a death cult going on. My Ministry for the Future talks about the Götterdämmerung syndrome, that if I have to change, if my way of life is going down, I'm taking the world with me. The Götterdämmerung is at the end of Wagner, the twilight of the gods. The Götterdämmerung is the auto-da-fé, the destruction of the world, because you can't stand the idea that your own power is going away.

It's a little useless to psychologize anything and say, this is the result of a kind of Freudian death drive. But on the other hand, when you're really mystified, it’s like “Why are people doing something irrational?” Then you have to remember we are all irrational and we all have unconscious drives towards prestige, towards security, towards various psychological statuses that are involved in this.

Well, I agree, yeah.

On a more positive note: your Ministry for the Future famously opens with a mass heat death event on the Indo-Gangetic Plain. Since we talked last year, I actually got the chance to go to India for the first time. I was actually in Delhi on the hottest day in its history, so far. And a combination of what I saw there and the global rapid clean energy build out made me feel more optimistic that we can hopefully avoid that kind of mass death scenario.

I'm sure you saw, Pakistan imported in just six months of 2024 over 30% again of its electricity generating capacity in new Chinese solar panels.

That's not just an emissions reduction thing, that's an adaptation thing. When I was in Delhi, it was really hot. It was like 115 Fahrenheit. But even a very small amount of technology can really, really, really help. I remember this little paratha restaurant by the Lakshmi Nagar metro station. On a super crazy hot day, it was this little oasis where people were sheltering. Because it was in a building, so it was in the shade, but it also had just one single electric fan. And just that little movement of the air brought it down to like 95 or 100 degrees Fahrenheit, which was a lot better.

I'm really hoping that in this race between clean tech and catastrophe on the Indo-Gangetic Plain, the huge wave of cheap solar panels from China will power enough fans and air conditioners to avoid a Ministry for the Future mass death scenario. What do you think?

I really enjoyed your reports from India! I myself was in Delhi in April of 2022, and it was a heat spell. I walked across the tarmac, and in that time, I felt that in a mere ten minutes how bad it could be. But it was also not dissimilar to a summer day in Davis, California. It’s possible. Humans are adapted to pretty high heat, it’s just that with climate change there might be spikes. The wet-bulb temperature, the combination of heat and humidity, if you get above wet bulb 35, then you truly do need technology to stay alive.

What India has proven is that people are extremely resilient to high heat and humidity, up to a certain point. If there's microgrids, if there's a solar panel on your roof, it doesn't matter if the grid breaks down. You’ve still got hundreds to thousands of people powering up air conditioners and staying alive. So maybe the mass heat death will be avoided! But the incidental deaths of the elderly, the young, the vulnerable in general, are still quite possible.

I would say that I wrote that scene six or seven years ago, and the situation has changed in India and in the world. But the danger remains. It’s just one symbol for all the bad things that can happen. Even if it won't be a mass catastrophe where millions die, it will only be a little catastrophe in which tens of thousands of people die, that’s not that good. We need to do better than that.

So something that we should talk about is carbon drawdown. Given where we are in the energy situation of still burning fossil fuels, to the extent of 40 billion tons of CO2 per year per year into the atmosphere, are we going to be able to draw it back down to get to safer temperatures for everybody?

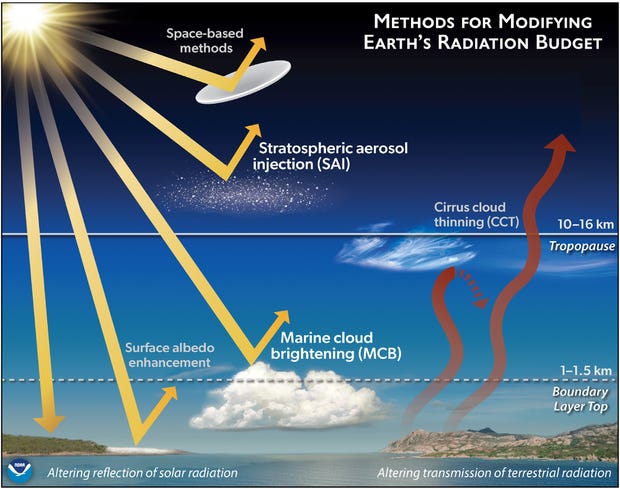

Also, in your novel, India unilaterally pursues a policy of stratospheric aerosol injection to cool the Earth. It seems like there's at least a non-trivial chance of that happening in the real world some time, maybe if India or China suffer a major heat death event.

And I'm starting to lean towards maybe that being a good thing. One of the major concerns about geoengineering was moral hazard, that it would stop other mitigation efforts. But the economics of clean energy are so good now that it's pretty clear that we'll be moving forward on clean energy whether we do geoengineering or not. Maybe just to avoid human suffering, it might be a good idea to pursue or at least experiment with some of the planet-scale cooling projects you've written about. What do you think?

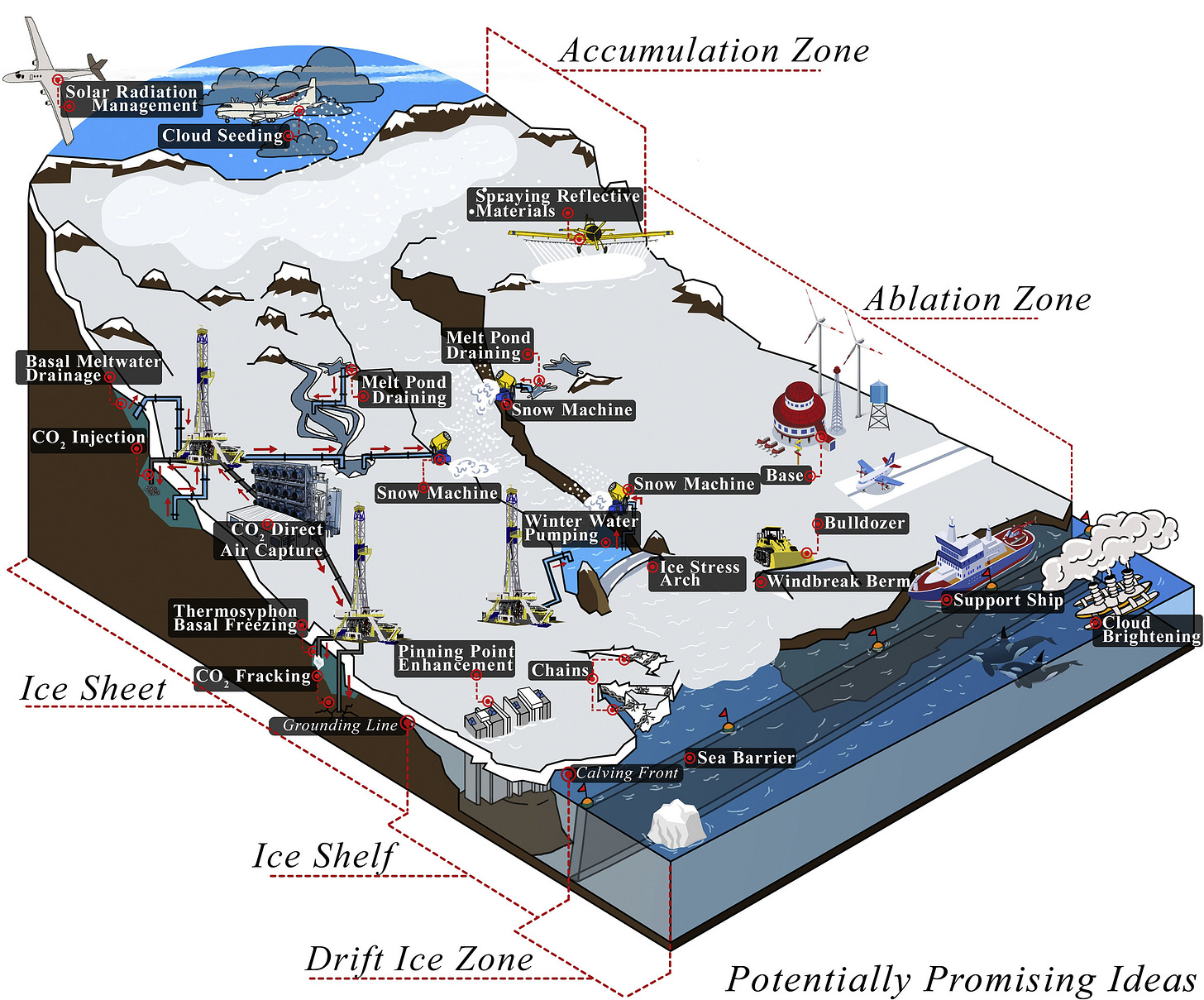

Well, it's been part of my job to track all of these things. There is a taxonomy possible of mitigations that can be put in different categories and arranged by their necessity, their priority and their dangers and effectiveness. Everything needs to be studied and put out on the table, I agree. The moral hazard argument comes from around 1990. Now, knowing what we need to do and not doing it fast enough puts us into a century of danger, what I call the carbon overshoot years, that it will take a century or even two to pull ourselves out of. To draw down that much CO2 from the atmosphere is a lengthy task that we should also talk about.

So in the meantime, should we cool the planet artificially? Sometimes geoengineering means solar radiation management, the casting up of dust or sodium or sulfur dioxide or some other substance into the high atmosphere to reflect sunlight into space. It’s a kind of cooling of a patient with a fever that might kill them while you cure the underlying disease.

I would say the first priority is reducing emissions, of course. That’s what we need to do, that’s what we’re not doing fast enough. There’s a new book by a Frenchman, Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, called More and More and More. It points out that the clean energy transition that you've been so good at reporting on has not [yet] been so much a replacement of fossil fuels but an augmentation. So far coal, oil and gas have not been going down [globally, although their use has been decreasing sharply in many countries and regions thanks to renewables] and we are fooling ourselves if we talk about it as a transition unless we really transition.

That reduction of fossil fuels to zero is the first geoengineering method, you might call it. Because it is an intervention, and it's an abandoning of a huge amount of capital and infrastructure, which is unusual for humans to do. Establishing the necessity of that is one of the tasks that we're not totally succeeding at because there's still people who don't believe it and fight for fossil fuels.

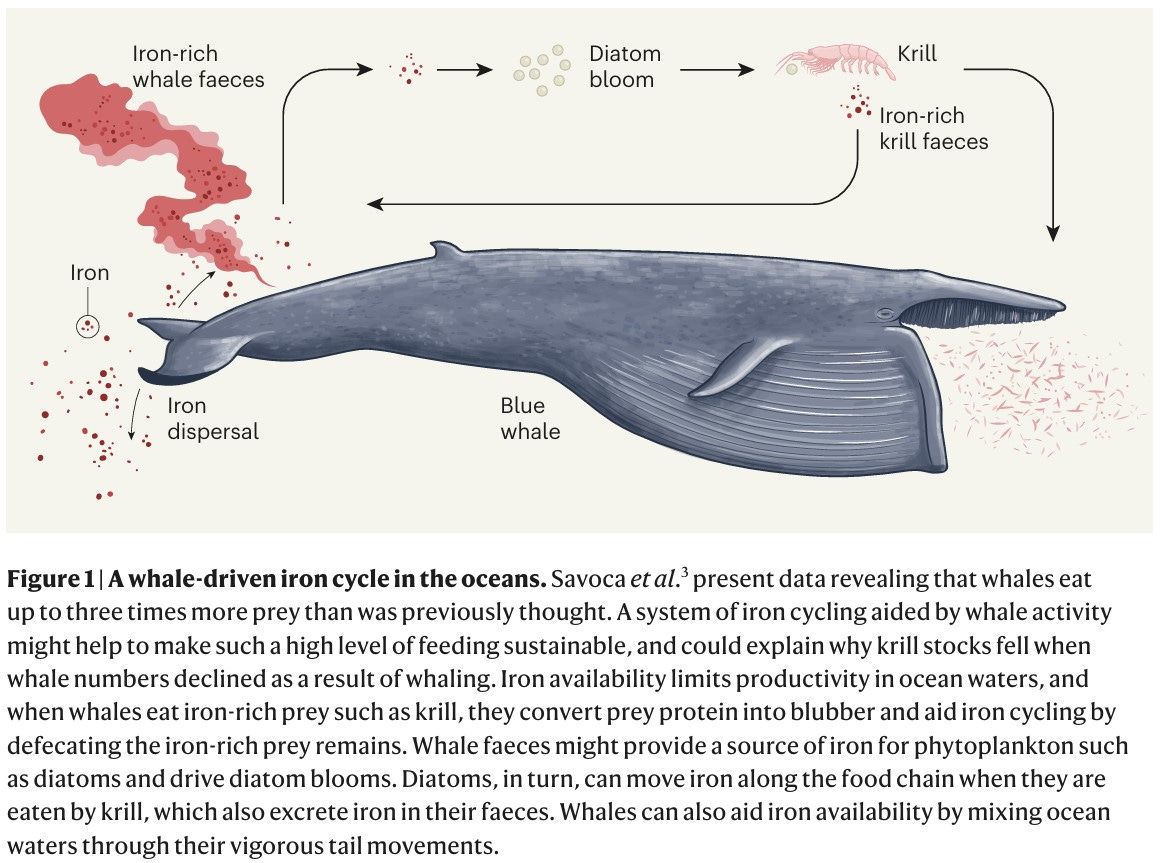

So that's number one in the taxonomy. Then number two: carbon drawdown. We can talk about all the different methods of carbon drawdown out of the atmosphere. Reforestation, regenerative agriculture, dumping dust into the ocean and creating algal blooms that sink to the bottom, seaweed, mineralization, putting gravel in the soil and olivine sand on the beaches to capture CO2. And then also machinery [direct air capture], these vacuum cleaners that suck CO2 out of the air and pump it into the deep earth.

All of these methods, not one of them is adequate by itself, because of the scale problems involved. They will all need to be employed. They'll all need to be paid for.

So that second category is worth investigating as a long-term necessity. There's no moral hazard at all to talk about the fact we’ve got too much CO2 in the atmosphere, and it has to come down if we want to be in a safe planetary space.

Then the third category, cooling the planet while we do these other things. That's solar radiation management. That's marine cloud brightening, which is much more regional and lower to the Earth, if every container ship left a contrail of bright marine clouds that were then reflecting sunlight back into space. Thickening of the Arctic Ocean ice, making sure that it doesn't turn into an ocean up there, if we could possibly do that, that too casts light back into the atmosphere. That albedo is crucial to keeping the temperatures from going up even higher.

So that too could be put in the third category of a cooling strategy, all ice preservation. And then one I want to talk about that’s almost in a fourth category: protecting sea level.

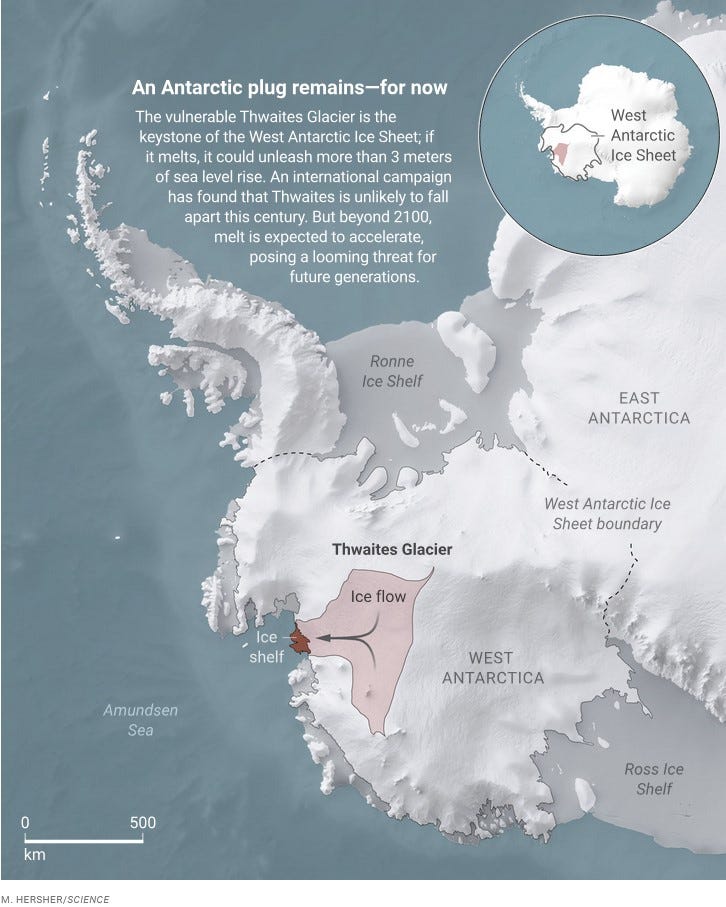

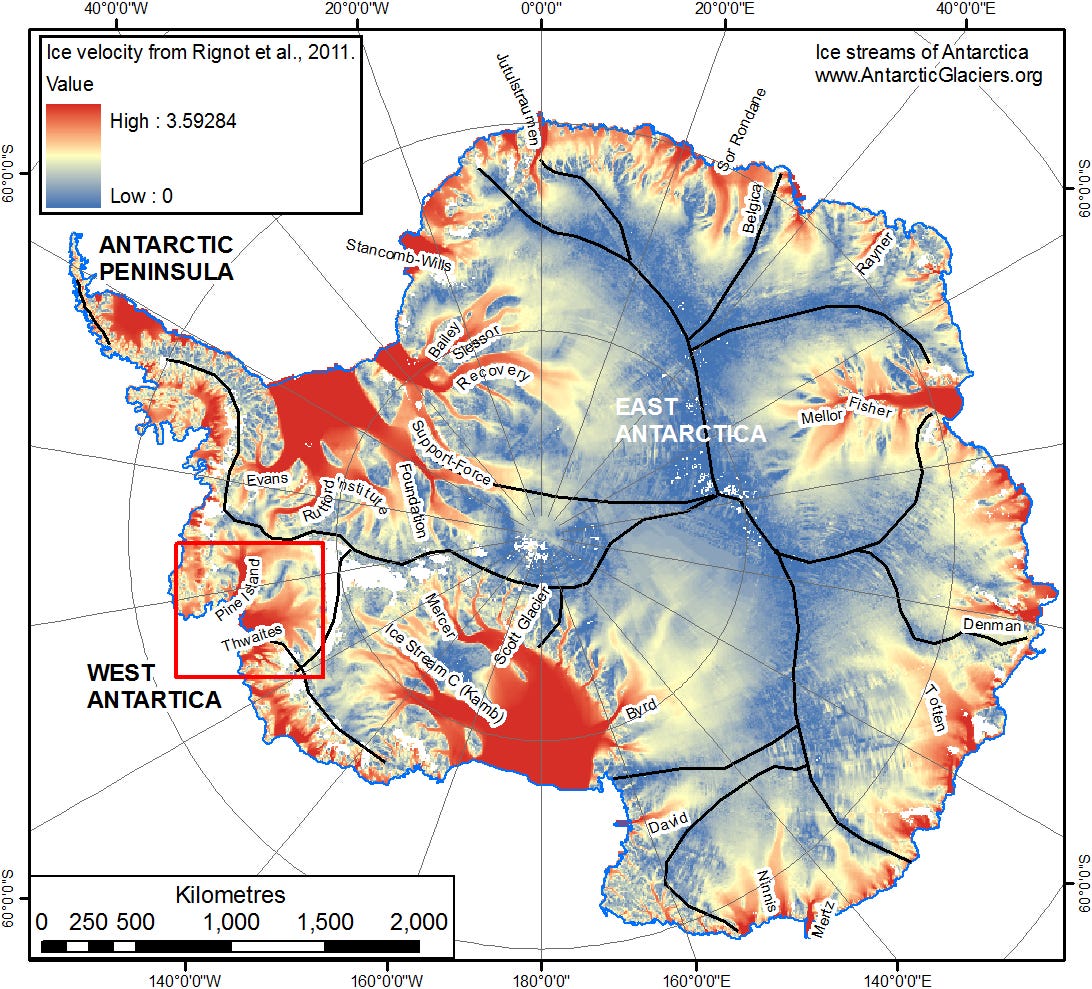

Sea level’s gonna rise. About a meter, because we've heated the ocean so thermal expansion is going to happen. We can’t stop it now, it’s baked in, in the most literal sense of that word. But if the West Antarctic ice sheet detaches, floats off into the ocean, and becomes water quickly then sea level worldwide could go up like four or five meters. For our American audience, what is that? That's 12 or 15 feet. That's astonishing and really bad for civilization. We are so devoted to our coastlines for trade, for shipping, for all the great cities that are right at the coastline that would be devastated, that we want the West Antarctic Ice Sheet to stay in place.

This is another one of these temporary gestures. If we can pin those glaciers down in Antarctica for 500 years, then in that time we might be able to cool the planet back down, or get in control of the Earth system. I mean control our own damage to it, get into a stable balance with the geosphere and the biosphere such that at that point the danger in Antarctica would be decreased to the point where we could perhaps lay off of that program.

That's what I've been thinking about recently. post-four years of talking and thinking about what you could loosely call geoengineering.

The reason I hesitate when I use this word geoengineering is because it's really become shorthand for the bad things that bad people want to do to get away with the bad things they did before. In other words, a negative noun, at least in certain circles. I want to abandon that noun or always modify it by talking about the many different things that it gestures to that are quite different in kind and degree.

A lot of people are saying “climate repair” now, not geoengineering. That focuses on the positive.

Yes, and climate repair is good in many ways. Sir David King at Cambridge has discussed, what if we were to cast into the ocean an artificial blue whale excrement? Blue whales, we almost killed them off [they’re starting to come back now!], and they turn out to be immense bio-pumps in the ocean ecology. They ate low, they pooped high. It brought a lot of carbon to the bottom of the ocean floor. So restoration, climate repair, these are good new names.

I think that for any scalable climate repair solution, it's a big advantage if it has a source of making money that is not related to its climate function. Like, not relying on selling carbon credits or something. For example, there's this startup Equatic. They pump seawater into an electrolyzer, run off clean energy, that can sequester CO2 and splits off the hydrogen from the water that can then be sold as valuable green hydrogen.

They're just starting up, but Singapore is making a big investment in them, they have a pilot project at the port of Los Angeles. They are a potential scalable carbon drawdown situation that could also make money, as it produces a valuable product that can be used. What are your thoughts on Equatic, if you've been following them?

Yes, I've heard of that. You're right. The idea of some of the products of CO2 drawdown being useful, an economic value and also a climate value, that's a great combination. There's an on-land company, Terraform Industries, run out of Southern California, its CEO who was a scientist at JPL when he started.

This is Casey Handmer?

Yeah! Casey's company is doing the same thing on land, where they draw down a CO2 and then split the chemicals so they've got a useful byproduct out of it. I’m glad you know about him.

With all these projects, the question becomes a sort of larger macro-question about all these possibilities. Can any of them scale? Can we convince people to pay for them and devote their work lives to them?

If it could be a job, and your job is somehow saving the biosphere, of course there'll be people ready and willing to devote themselves to a career like that. It would be meaningful. And if you can make your living, fantastic!

Can we pay for it? There I think there's some flex. As John Maynard Keynes said, anything we have to do, we can afford to do. But he wasn't talking about runaway greenhouse effects. We have to save ourselves from a runaway greenhouse effect, we have to make sure we stay inside those boundaries and stay in a realm where we can bring us back into a livable space.

To pivot slightly, there's one really interesting discovery that I don't know if you followed, but it seemed very much like a Kim Stanley Robinson sort of plot mechanic to me, except in real life. That's the possible discovery of dark oxygen. The discovery that a bunch of mineral nodules on the ocean floor appear to be having electrochemical processes such that these rocks are basically just bubbling off oxygen at the bottom of the ocean. And there's been excitement that this could be a source of oxygen, hypothetically, on Europa or Enceladus. The fact that this exists could really change the potential habitability of the entire universe. Planets far enough out from their suns that they can't really get photosynthesis going could have a source of oxygen through electrochemistry like this.

This also is really policy relevant for deep sea mining. I did an interview a couple years ago with a company that’s trying to do a low environmental impact version of deep sea mining, using “tweezers instead of a bulldozer” to just gently pick up mineral nodules instead of scooping them up with bottom trawling.

But now, maybe these aren't just rocks sitting there, maybe they're underpinning parts of the ocean ecosystem that we don't know about. Maybe this might be related to dark fish, the idea that there's a lot more deep sea fish than we think.What are your thoughts on sort of the dark oxygen discovery and its potential implications?

I'm interested to bring it up from that angle of oxygen, because we've got our 21% in our atmosphere and we don't want more because it makes us more flammable. We don't want less. It's a homeostasis situation.

I'm much more familiar with the deep sea mining for manganese nodules and other kinds of rare minerals that we need for batteries and for human civilization. that are possibly widespread on the deep sea floor. I'm glad to hear you say that about tweezers rather than bulldozers, because it seemed always to me that if we were to interfere and to mine the deep sea floor, that it would be the time to do it cleanly. It would be very easy to pluck nodule by nodule, it might just be more expensive.

The trawling of the bottom, it's just scraping the whole thing and destroying everything for the sake of getting one thing. We've already done that in the shallow oceans, it's devastating, it's bad. Anytime you wreck the Earth to take something valuable, you make a profit, but that profit is a form of theft from the future. It's a bad algorithm. Deep sea trawling was one manifestation of a very common category error we've been making since the 18th century at least, if not forever. What if deep-sea use was a kind of non-profit activity? I'm interested in all processes like that.

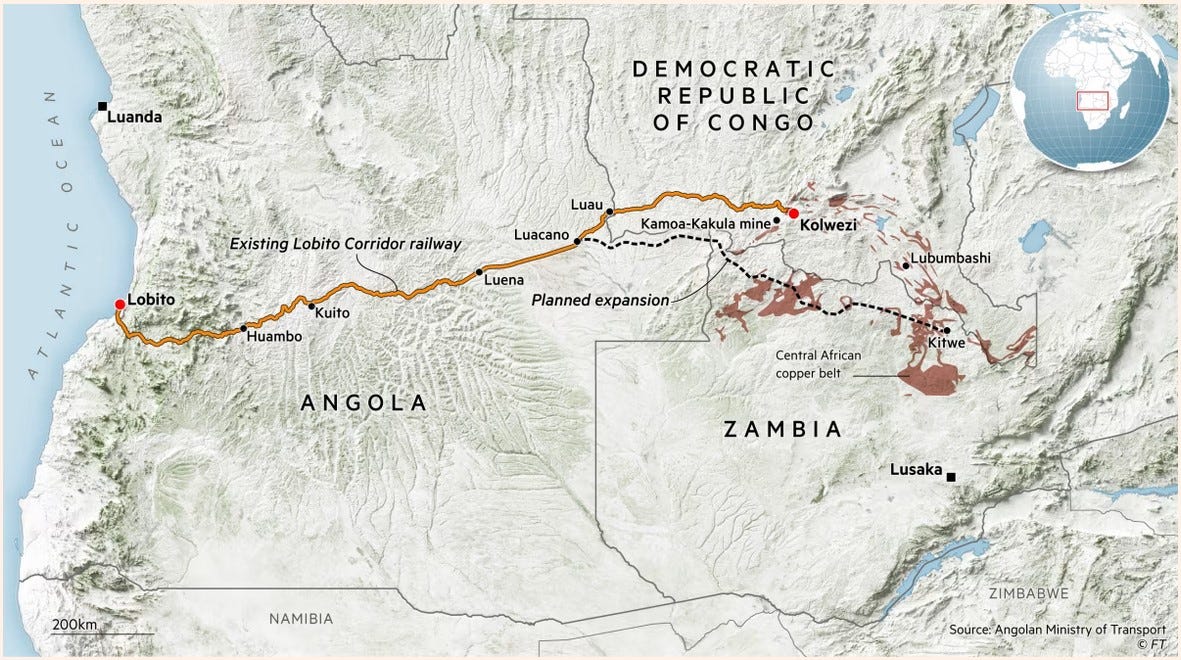

Speaking of the minerals we need for batteries, I'm always surprised that the climate community hasn't talked more about the Lobito Corridor. That's potentially a really big investment in creating a railway from the Atlantic in Angola to the Central African Mineral Belt in the Congo and Zambia.

Of course, there will be environmental damage at the site of those mines, but based on what I've been reading, it will probably on net be a substantial benefit for the people of those countries. Development money that’s already been committed would help pay for grain silos, solar microgrids and more along the railway path. [This may be disturbed by ongoing U.S. government chaos]. And it will potentially supply a big chunk of the copper we need to transition the world to run on clean electricity.

Well, I think that there’s a few things going on there at once. There’s an American provincialism, that nothing really significant is happening that isn’t in America. There’s a focus on the intensely interesting and problematic dynamics going on in this country, so that knowledge of the world…even in really prominent places, even the major media that are relatively good on the international front are pretty bad at it. New York Times, Washington Post, they don’t attend to the rest of the world very well, and much of the rest of the media doesn’t even try.

Sub-Saharan Africa is crucial to this next century. The population growth there, the potential for pandemics, the resources that are there are incredibly important and growing more so, all in one rather small area that our newly inaugurated idiot of a president calls “the s**thole countries.” America’s not gonna be good on that front. The idea of the “dark continent” from the 19th century, that attitude has never gone away. Even though this is a crucial part of the planet, for multiple reasons, and will grow more so as they power up, as they get clean water and toilets and energy supplies that are solar-based and widely distributed. As that area begins to prosper, the world begins to prosper along with it.

One of the things about your column is this internationalist thing, the attention to what’s happening elsewhere. You and Mongabay do this, and it’s what we need to hear in America. We really need to know that the world is so complex that good things are happening everywhere, particularly on the biosphere front.

There's currently a vogue among many people, Elon Musk being the most famous, to say, “Oh, the real problem in the world is fertility rates declining, that's a bigger deal than climate change, humans could go extinct!” I wrote an article a while ago that just said, everyone chill out about population numbers, because that just seems to me to be so wildly overhyped, the idea that fertility declines are some kind of existential threat.

As the great Substacker Noah Smith recently said, due to the nature of population growth, because it's compounding on itself, if you extrapolate the trend at any point, it is always either going to infinity or zero, Like, if there's fewer people, then they have fewer kids, and so on, and you can project that out to zero. And if there's more people, then they have more kids, and so on, and you can project that out to infinity. But that doesn’t actually happen in real life. Things change.

Just a couple decades ago, we were worried about massive overpopulation, and now fertility rates are going down pretty much across the world very fast, due overwhelmingly to more freedom and choice and healthcare access for women, and now people are freaking out again? I've always thought that that is a massively overhyped “threat.”

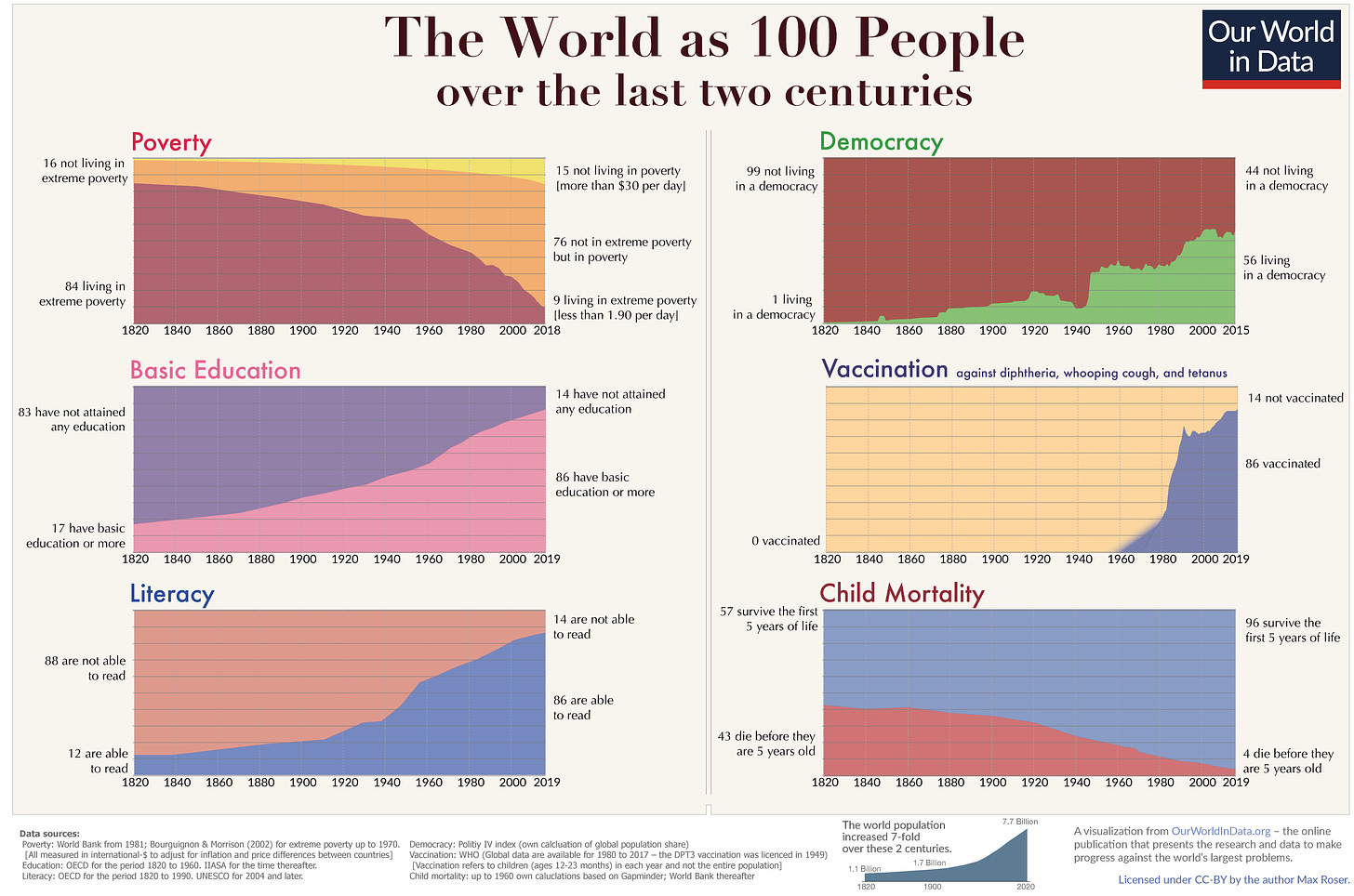

The closest thing to a good argument I've seen that fertility declines are a threat is that fewer people means fewer scientists and innovators and people who might come up with the next big idea. But the real way to fix that is solving extreme poverty, freeing people who are gathering firewood and selling it in the street to study math and science and do stuff with that.

Obviously, it's a big shift, the global demographic transition is a huge deal, but I don't think it's a bad thing. What's your take on this?

Well, let's not spend too much time on this, because it is too stupid. The Earth's human population just 50 years ago was three or four billion. We are in a population overshoot that is uncomfortable to talk about because however many people there are, we have to take care of them. We are one of them. All of us need to do well together.

And as you pointed out, the way to grow more scientists is better education. The reason that population is beginning to level off and might drop is because of women's education, because of women's legal rights. This is a double good. The replacement rate is 2.2 kids per woman, and in all the developed countries they’re going below that naturally with no legal pressures whatsoever just by women pursuing their lives with their partners in ways that are best for them.

Really anytime you have an argument pursued by Elon Musk at this point, you're well justified in being suspicious of it. The whole thing about “Oh my gosh we might have a population drop how horrible?” These people are not ecologically trained. They're not thinking. It's a kind of false alarm. It's another way to distract us from the huge dangers of climate change.

Yeah, I absolutely agree. And in a lot of places, this creates a huge virtuous cycle. It can reduce some dependency ratios, fewer kids per working adult means you can develop faster, which means people get more education and healthcare, which often means you have fewer kids, and so on.

And this might be really good for workers. Since the Industrial Revolution, a lot of the treatment of people is based on the idea that if you don't want this job, there's another person who does along in a minute. With a smaller population, maybe we get a world where job interviews consist of people holding auditions for which company can make them the best offer. We’re already seeing this some places; thanks in part to Biden Administration policy and thanks in part to demographic shifts, fast food jobs in the U.S. now pay better than they ever did. There's a higher demand for just low-skilled labor because there's fewer people doing it. I'm thinking that if there's fewer people, through just supply and demand, each individual person is more valuable and has more economic bargaining power.

You can just call it full employment. Full employment matters. A targeted 5% unemployment rate was established to instill fear in the heart of the poor, who will then take any job, including what Graeber called bullshit jobs, in order to avoid starvation because there's no social safety net. Fear is one of the control mechanisms that creates a “realism” where the poorest person will say, well, it can never be different than this.

We could get full employment because there aren't enough people. As you point out, you could begin to interview companies rather than companies interviewing employees. If they wanted you bad enough, you would get a living wage. This is a crucial thing that everybody ought to have. And that higher value for labor would help the poorest half a billion people on the planet, who are still living day to day, hand to mouth in what the UN calls food insecurity.

A business school will say, well, you've got to have wage pressure. Well, what's wage pressure? It's fear in the hearts of the unemployed. That's what wage pressure comes down to.

So fewer people, more value of human beings, more ability to become themselves by having a certain amount of social security and probably a meaningful job rather than bullshit jobs.

Better than that would be everybody thinking of their job as being meaningful in the larger human project of coming to terms with the biosphere, and that's another kind of utopian goal that needs to be put on the table time after time. It's not just a matter of making sure that you've got rent and water and food. It's a matter of having meaning. That doesn't get discussed enough.

In the U.S. right now, for example, one really meaningful job is being an electrician. In a lot of places, installation of rooftop solar or heat pumps or electric vehicle chargers is bottlenecked not by money, there's a high demand, but by number of electricians. Because we're electrifying the whole world!

There's this long history of viewing manual labor and factory work as immiserating and precarious and low status. But as Elle Griffin’s been pointing out on Substack, the reality of that has flipped thanks to automation and a bunch of other things. Today, working in, a battery manufacturing plant or being an electrician is often a pretty good job, pretty safe job, very well-paying job, and a really meaningful job because it helps with electrification. That's a category of meaningful jobs we could use more of.

That's so true, and I'm glad to have you describe it that way. My brother is an electrician, and I've often talked to him about it. There’s voltage that can kill you. You have to be careful. It is athletic. It involves physical skills. It is also intellectual, scientific, you become like a detective in a detective story. I've got a mystery here. How do I solve it? So it has an intense cognitive aspect to it.

What was often said about factory work was you were just a living robot doing one thing over and over again. Taylorism, the assembly line floor, it was routinized and you were only doing part of it. Well, electricians are often involved with a huge range of the installation. They are not being atomized into just a part in a big machine. They're actually an active agent out there in the world doing complicated things. The job satisfaction at the end of the day and pride in work is extremely high.

But you talked about this, status in our culture. What then do they do when they go and they look at their social media? They need a social media that is aware of them as worthy citizens with meaningful jobs. If there happens to be a slice of the society that is dismissive of physical work in the real world, as obviously important as it is, then they will be repelled by that or even offended by that. And then anybody that tells them that they're worthy, even if these are sleazy opportunists who are really trying to grab their votes and their money, they'll nevertheless be attracted to that just because they're being appealed to.

So in the United States, how does the Democratic Party make sure that it is attentive to all of its citizens that are doing important work, no matter what they're doing, so that those people can't be snatched away by false appeals to being somehow more patriotic or more macho? Even rather ugly appeals, if it's the only appeal you have that regards you as worthy, of course you're going to choose that over people that are utterly dismissive of you. So this is a story to be told, a political story, I think.

Absolutely. We need to valorize blue-collar work again, both because it's both good politically and we just need it. We need more smart young people to choose being electricians. I know that I am obviously saying this while not being an electrician and doing a laptop-type job writing about stuff online, that is stereotypically the sort associated with the Democratic Party. But we really do need more people in the trades.

Seriously: if you, the reader, are at a loose end and looking for a meaningful job, consider becoming an electrician!

I do want to talk about the situation in Antarctica and describe that project in more detail.

Please do!

Things have been happening with my Ministry for the Future that have been exciting! There is now an Oxford Ministry for the Future that is a think tank and discussion group at Oxford University. I'm doing stuff with the UN, because they've established a Pact for the Future and are hoping to appoint an Envoy for the Future. All of this I'm associated with.

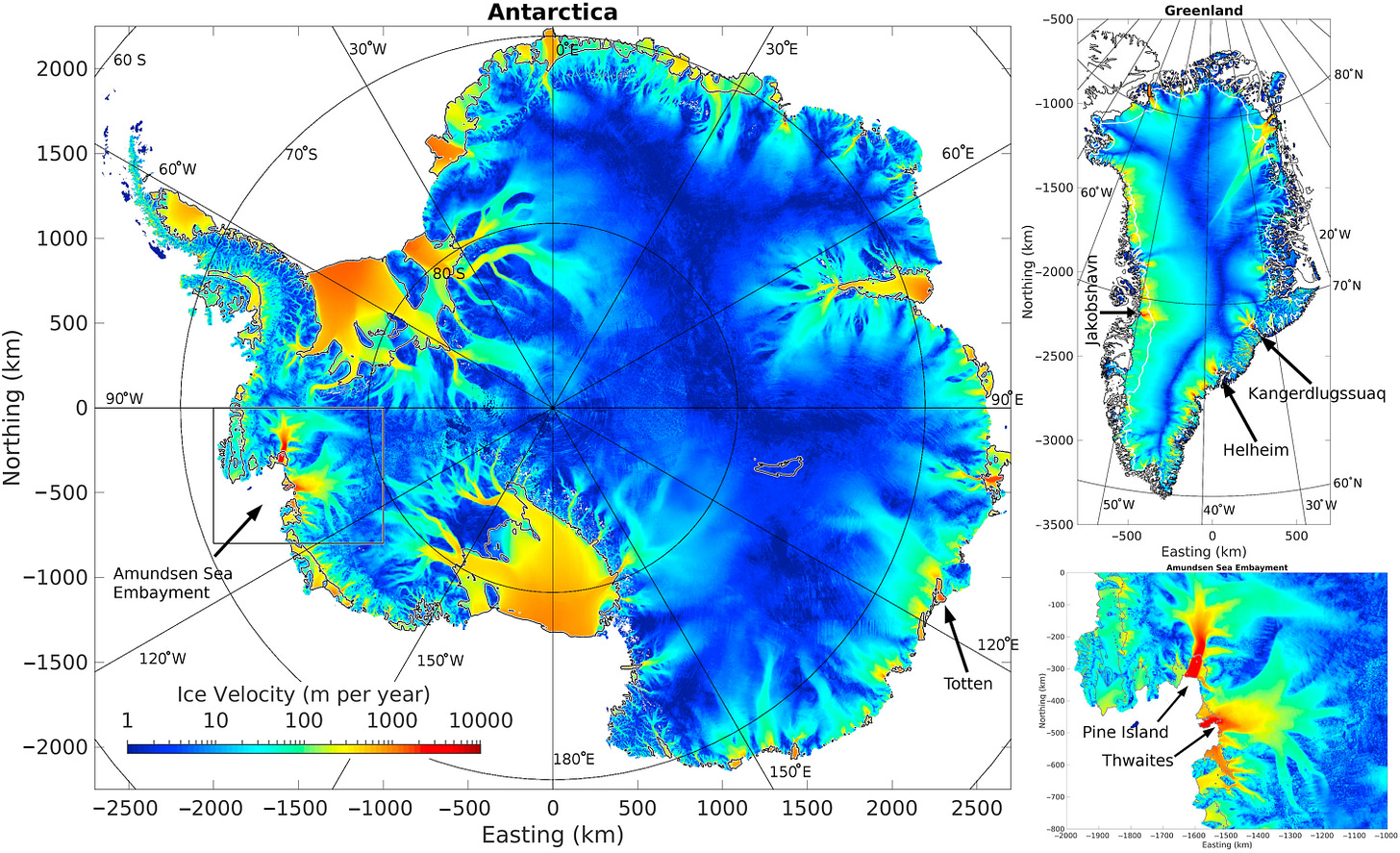

But one of the most exciting projects is a more tangible thing. It's physical in the world. Those big glaciers in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet are speeding up. And the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is a massive cake of ice that rests on land that is below sea level. In many parts of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, it's volcanically hot, it's a rift zone, so it's kind of warm down there and could be volcanic. But also, the ice is so thick and so heavy that it's resting on land, yes, but that land is below sea level. So it's unstable.

In the past, like three million years ago, it was water and then it kind of built up to the point where the glaciers came down out of the Transantarctic Mountains and they covered these lower zones and they stayed there. And that built up over time, long periods of time.

But when temperatures get hot, when the CO2 levels in the atmosphere get as high as they are now, historically, in the past, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet has detached and sea level goes up, as I said, something like four to six meters. So this is dangerous and we're in a danger zone for sea level rise.

Now, a group has come together. It's a combination of glaciologists and technologists from Silicon Valley, also financial people, and then also a group of internet and computer experts who are interested in doing things to help the world, which started a kind of a Saturday morning Zoom pandemic club amongst friends. They've all coalesced into a non-profit, a 501c3 now, called Ice Preservation.

The notion is this. There's one gigantic ice stream that was moving fast into the ocean, and about 200 years ago it stopped dead in its tracks. That part of West Antarctica has stayed stable and has even accumulated ice since then. The explanation appears to be that the water streams underneath the glacier were diverted. In any place you get braided streams, like in riverbeds, sometimes a channel will go dry because its water got stolen. Apparently this Kamb Ice Stream came to a halt and has been stuck in place ever since, like a plug holding up the ice behind it on that part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

So the question that this group is trying to pursue is this. Could we pump out water from underneath the Thwaites Glacier and the Pine Island Glacier? These are the ones that are moving really fast and could break up and destabilize the entire West Antarctica. Could we steal the water from underneath those glaciers, and/or put down thermosiphons that are essentially like long skinny heat pumps and freeze the bottom of the ice stream to the rock underneath it and slow it down thusly? Either way or both. Could we slow down those big ice streams to the point where West Antarctica was stabilized?

Now, the stabilization might have to be maintained. And there's still going to be a lot of ice that is moving to the coasts. And the Antarctic Ocean is still going to be warming up. So there were other plans being pursued by other groups, for instance, in putting sea curtains across the bottom so that the warm currents don't come underneath the glaciers and warm them from below. Possibly a worthy effort.

Our group is aware of the other groups, but this group is focused in on only basal stabilization of the glaciers of the ice sheets. There are some glaciologists who flatly deny that that's possible, that that could work. It's mysterious to me why they say that, because we don't really know.

But all the glaciologists would agree, we've never tried an actual intervention. We don't know if we could do it. We have the tools and we have some information. And so this group, Ice Preservation, is working on an experiment that would be in the North, in Alaska or in Greenland or in Iceland or in Svalbard, where you would try a test of the methods and see what happened to the smaller ice sheet in the North, which is more accessible and which has a different legal regime.

So the experiment comes first. Then after that, the discussion with the larger world community, is this something worth trying or not? If it was to be tried in reality in Antarctica, there's a little bit of a window of time, so it isn't like it's extremely urgent, but it should be done within the next couple of decades if it's going to work at all.

At that point, you would need massive logistics that would involve navies. The U.S. Navy has been logistical support for our Antarctic efforts all along. And their seaport bases are all right at sea level, obviously. One interesting thing going on for me personally is that the U.S. military is beginning to understand that their charge to defend the United States might include defending the land of the United States and even the sea level of the United States. And they, of course, have massive expertise, massive budget, massive logistical abilities. They are not capitalist, they’re not out for profit, they’re out to defend the United States. If that begins to include the biosphere of the United States, then we've got a big power system there to help.

So that's my own angle on this Ice Preservation project. I'm kind of a reporter, I'm part of their meetings, I'm doing kind of like what you do, but in this very limited way of being focused just on that.

This is amazing!

It reminds me of the work of Dr. Leslie Field and the Bright Ice Initiative.

They’re doing more mountain-focused ice preservation, basically using shiny sand to reflect light to protect glaciers. Do you think there could be some synergies there?

Well, I love it. This is a little community of like-minded people There are several organizations now, and Bright Ice is one of them. There’s another one, Operatio Arctis, which is in Finland, they’re thinking of preservation of the Arctic sea ice principally. They all realize that preservation of the cryosphere is important, and that one project helps another. There are groups at the University of the Arctic, and at University of Chicago under David Keith, that are focused more on this seabed curtain method of helping glaciers or ice shelves in Antarctica.

The group that I'm following, Ice Preservation, is well aware they're part of a little ecology. that includes all these people. There's a group at MIT that is interested in these projects, and so on and so forth. So it's a growing community of organizations each taking a different aspect of the problem of the cryosphere, and Bright Ice is one of them.

This is fascinating. I can't believe I hadn’t heard of Ice Preservation before!

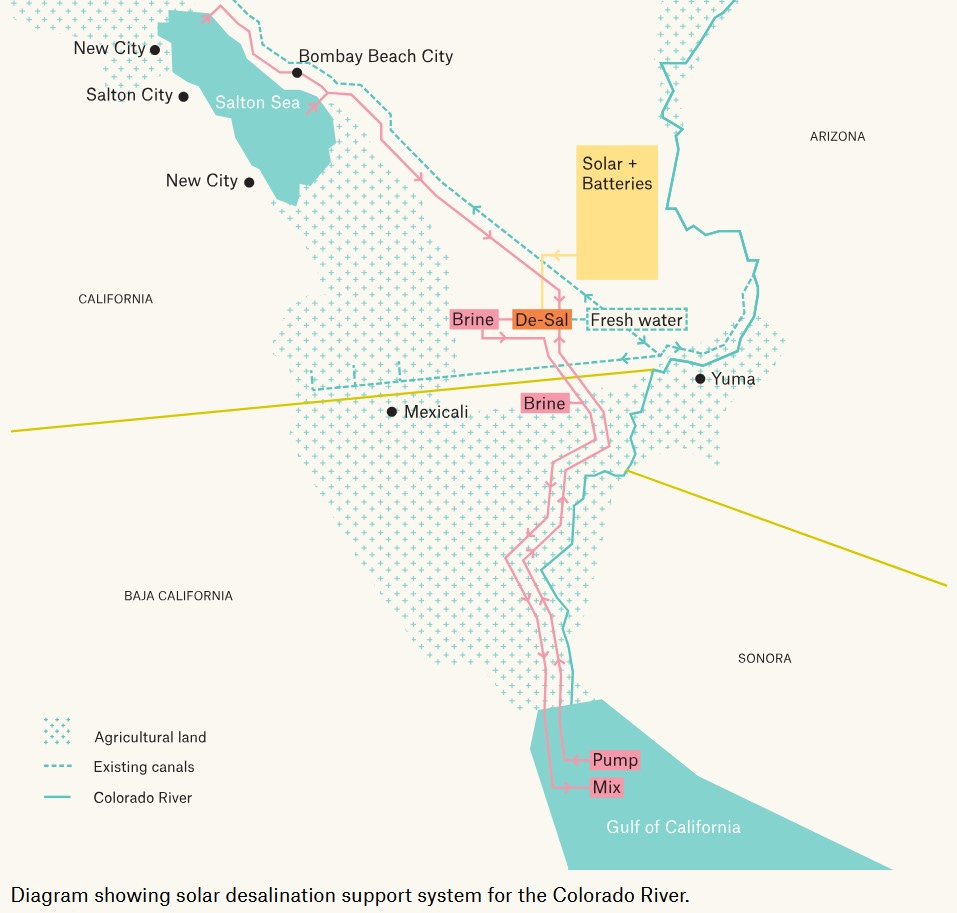

One of the potential huge benefits we could get from the explosion in solar power is cheap desalination. You mentioned Casey Handmer, he's written a lot about the potential for solar to power much larger desalination efforts, like potentially refilling the Salton Sea and pipelining desalinated ocean water into the Colorado River Basin to keep the U.S. Southwest hydrology functioning.

A lot of countries, especially in the Middle East, are starting to depend on desalination just for drinking water. Fortunately with solar power, they can now power that fairly cheaply. In Spain, they’ve invented floating desalination plants.

What's your take on the potential for desalination to provide abundant water and synergize with the clean energy revolution to help prevent water shortages? And not just for humans, but potentially even for at-risk freshwater ecosystems.

This is an interesting test of the whole human civilization. Because to a certain extent, it's a kind of rich versus poor situation. Obviously, clean renewable energy, if we had a lot of it, we could do a lot of great things. If it all gets burned on chasing AGI, etc., when there are still people without clean water, without toilets, then it's a sign that some people are just choosing to ignore the immiserated that are still on Earth.

There's a fight amongst people of goodwill on focus. The narcissism of small differences is a real thing. Allies fight all the time, sometimes more viciously than they fight against their common foe.

I've really noticed that, yes.

So desalination would be great. We do have the capacity for cleaning the power in the necessary places. It could be devoted to these kinds of ecological repair projects, and just fresh water in general for people who have tapped out their groundwater or fossil water, it's important.

But it might be that many of these projects...we can talk about good things like desalination, but if we're still burning fossil fuels, it's a bit like putting a Band-Aid on a cancer patient. And as a utopian science fiction writer, of course I'm prone to falling into this error.

What I worry about is what has been usefully called hopium. You provide hope by showing us real things in the real world that are going on right now that, if they succeed, we will get out of this century without a mass extinction event. Now, we need hope and these things are real. I'm not saying what you and I are doing is wrong, as a kind of utopian political project of saying pessimism is wrong, cynicism is wrong. despair is wrong. What's right is fighting and pointing out how many other people are fighting for good things.

I guess I'm encouraging myself, in our discussion of the whole world of positive news. to make sure we don't ignore the realities of the power of the fossil fuel industry, the dangers that we're still in by putting 40 billion tons of CO2 into the atmosphere every year. That endangers all of our good projects to an extent.

We must also focus a good bit of our energy on defeating the fossil fuel industries and their authoritarian governments around the world. Climate change forced by fossil fuels might cross the big tipping points, might throw us into a runaway greenhouse effect. We must win the fundamental battle of reducing emissions and retiring the fossil fuel industry, which is a gigantic challenge and needs to never be forgotten as task number one.

That's a sine qua non, “without it, nothing.” Rapid emissions reduction is a sine qua non for everything else succeeding. So one of the good stories we need to start telling is how people are convinced to support what is effectively a pro-earth, pro-biosphere, political program. It's also, obviously, pro-people.

I agree with you about not portraying everything as sunshine and roses, but I also feel like there's really strong structural incentives in news to inherently portray everything as apocalyptic and doom. Most sources of news are really biased towards despair and cynicism, and that breeds inaction.

This guy I interviewed recently, Jason Pargin, said if everything's screwed already, then you don't need to do anything. Telling people that everything's terrible is actually a sedative, an excuse not to do anything, because nothing can make a difference.

Hope is necessary. I try to point out, we have points on the board! EU power sector emissions have declined by half since 2007. Decoupling is bigger and bigger across the world. There is meaningful progress, even though there's still that huge amount of things to do.

We need almost a double vision of “we've made amazing progress and we're in a huge problem that needs more and faster amazing progress.” But that's different from saying everything's screwed and nothing matters. I'm trying to find that balance there.

I'm with you. I regard this as working on the same angle of the project. Writing utopian science fiction that still feels realistic is a balancing act, to put it mildly. And I'm devoted to it. It's been my career. People need the positive as orientation to what do they do and also to not give up.

I think you're right. The mainstream news, if it bleeds, it leads. And the whole doom scrolling and the clown show of our president, the world as reality TV rather than reality, that needs to be opposed by a consistent press of, wait a second, there are good people doing good things and good results are happening. There are some wild creatures that are doing well because we help them in ways that are counterintuitive to older notions of pure wilderness or pure nature. The Anthropocene can be a good one if we make it so!

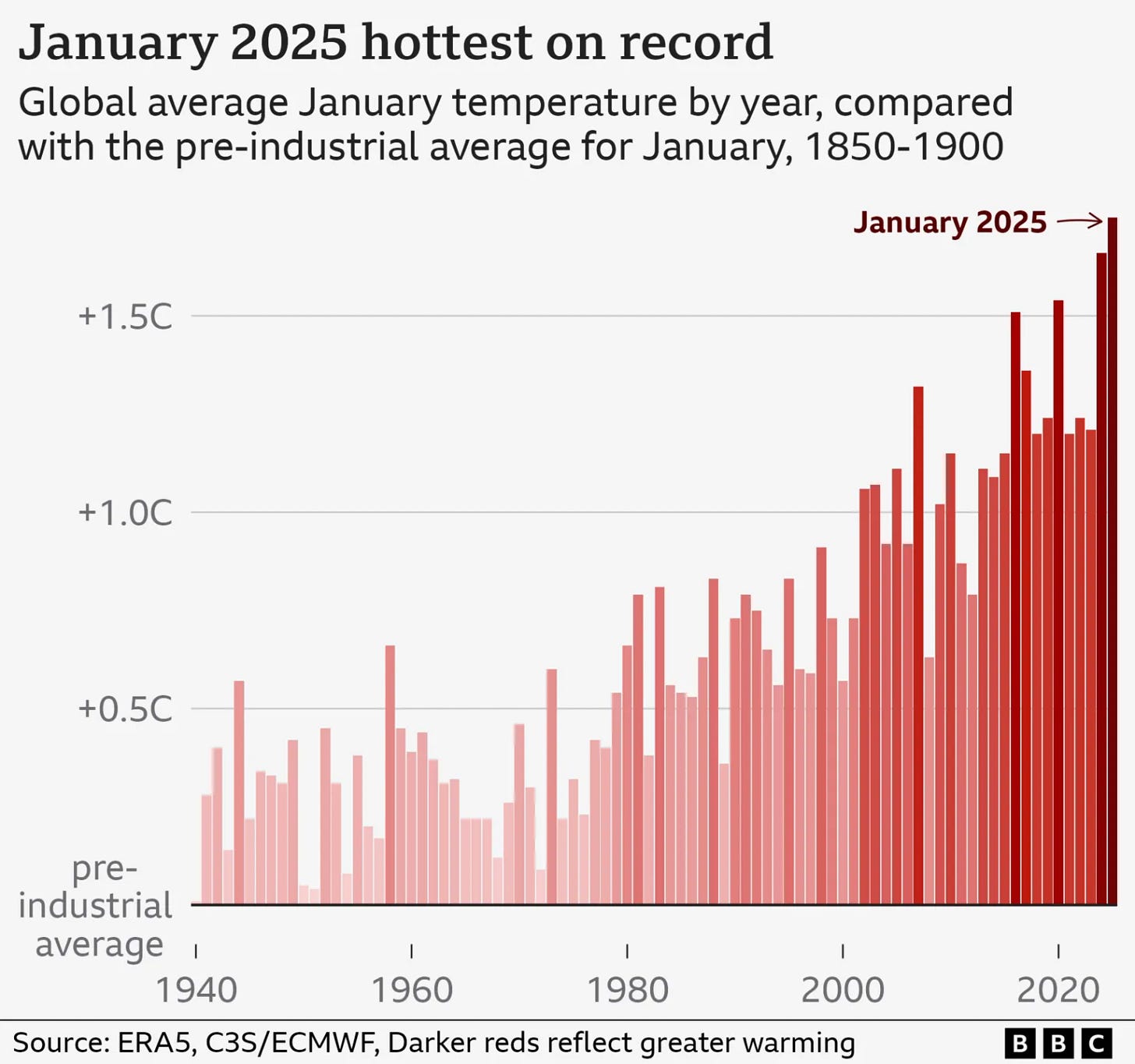

One thing that's really encouraging me is that while climate change is getting far worse, while we are passing 1.5 and seeing all sorts of terrible stuff, a lot of the really key things we need to address some of the threats via which we're most worried about climate change killing people are also developing really rapidly.

Like malaria vaccines, one of the biggest potential avenues through which climate change could kill people is expanding malaria habitat again. Malaria vaccines have been developed and are spreading really rapidly. That's a really big deal.

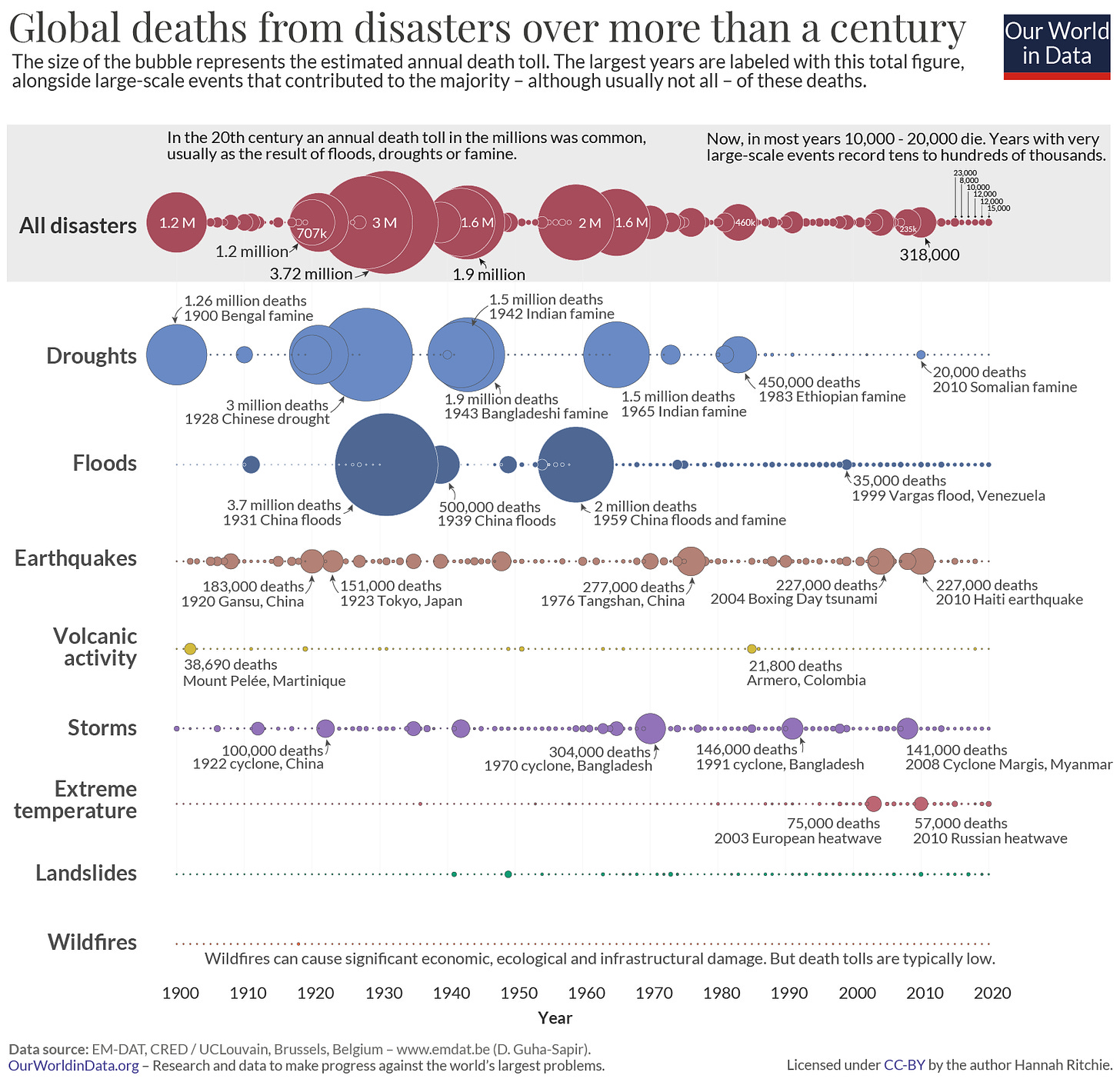

And climate disasters, even as the storms have gotten worse and the fires have gotten bigger and the rain has gotten more extreme and the droughts have gotten more extreme, fewer people are dying of disasters than ever before! Thanks to smartphone warnings and weather satellites and community warning systems.

One example: when like Cyclone Bhola hit Bangladesh, then East Pakistan, in the 1970s, something like 300,000 people died. But when a bigger storm, Cyclone Mocha, a storm supercharged by climate change that was Category Five compared to Bhola's Category Four, hit in 2023, only a few hundred people died. A factor of a thousand less. Because Bangladesh had deployed an early warning system, and even if you have only one person with a phone per village, that's enough to tell people to get to higher ground, to get to shelters.

There's almost this double vision effect. Even as the effects of climate change get worse, even as things get hotter and more chaotic with worse storms and stuff, we might also see fewer people dying. Because that's what we're seeing now!

That doesn't take away from the the reality that the climate change is a big deal. But it does help. And cheap solar panels account for a huge amount of this, because they can power like basic air conditioners in the tropics, they can prevent mass heat death events.

While we work on the centuries-long project of carbon drawdown, I'm feeling encouraged that from malaria vaccines to innovations in agriculture to weather warnings to cheap solar panels, there's a lot of technologies that can maybe keep the human death toll from climate change much lower than we were worried it would be.

Well, I find that very encouraging, what you say. And I always use that word reminding people to run it back in its etymology: it infuses me with courage. We want to give people courage to fight onward and harder. And that's what you do. And that's what I'm trying to do.

One thing I've been encouraging myself with is that even the president of the United States is limited in their power in the world civilization, and this is a century-long effort. You can't dismiss the loss of four years, but it won't even be a lost four years. The United States has never been, except under Biden, a climate leader. The rest of the world has done the things. The economics comes out of China. The EU is the political organization that cares the most. India is under immense pressure to get this right. Same with Brazil.

The warning signs are obvious. The positive signs are a little bit more under the radar and underreported. So we just have to carry on, I guess, fighting the good fight. Certain aspects of my message to the world need some quick rethinking and some quick updating. And we just need to keep going on. Even in the current situation's almost embarrassing American context right now, there's a larger world context and there's a larger world history where it's just something that we have to fight on our own front and do the best we can.

Absolutely. Is there anything else you'd like to add?

That was the news I wanted to bring to your audience. That interesting things are going on. That geoengineering is not the right word anymore, as opposed to climate interventions or climate repair. And that each proposed project needs to be evaluated on its own merits and dangers, not always pouring them all together into one pot and then saying, “we shouldn't mess with the atmosphere, we shouldn't mess with the oceans.” We've already messed with the atmosphere and the oceans quite substantially! So efforts at repair need to be all on the table. Amongst those, this ice effort is interesting, because it would be very nice if we could avoid massive sea-level rise. That's the main thing I wanted to talk about, and I think I've made that clear.

Thank you. I am just incredibly honored that you read my newsletter and that you like it and that you wanted to be interviewed. Thank you so much.

My pleasure. Thanks for what you're doing.